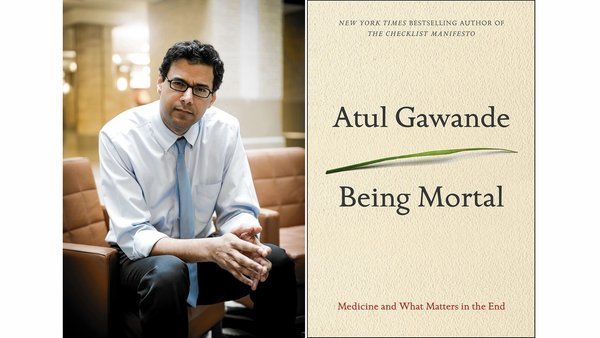

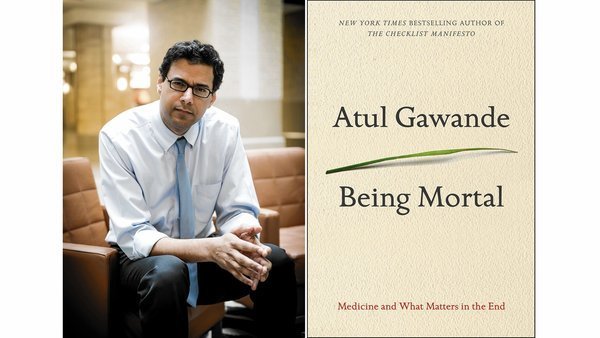

Book Review: Being Mortal – Medicine and What Matters in the End

30 Mar 2017

Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End is not exactly holiday reading. With the surgical precision befitting a man of his trade, Dr. Gawande regales his readers with the process of human bodily decay – a calm descent from the greying of hair to the hardening of arteries – by chapter two. The tale of our inevitable decrepitude is always best left imbibed when not relaxing on a beach, but this is certainly vital reading for all who happen to be human.

In this brilliant, moving and thoroughly compelling book, Gawande deals with fates far more controversial and complex than death: surviving versus living, compassion reform in a new era of medical technology and how we ought to approach the inevitable end.

According to the author, there were a few catalysts for his fourth best-selling book. Surgeon, public health researcher and staff writer for the New Yorker, Gawande noticed an increase in what he terms the ‘medicalisation of mortality’ through his work and research. He struggled with not knowing how best to treat patients whose problems were not able to be fixed, whose ailments were that of old age or terminal illness. Confronted with his own father’s mortality after the discovery of a tumour that would ultimately lead to his death, the procedures required to prolong his life would detract significantly from his quality of life. What should someone be willing to sacrifice for the sake of longevity?

Gawande outlines the difficulties we face now in a progressively modernising healthcare system – a growing elderly population, a lack of geriatric care and an inability to know how best to treat those nearing the end of their life. Geriatrics and palliative care are hardly the sexiest in the medical arenas to move into, after all. Gawande interviews Felix Silverstone, senior geriatrician at the Parker Jewish Institute, NYC who says with honest resignation that “old age is a continuous series of losses” – hearing, memory, friends, autonomy, bodily functions. When irreversible conditions and losses are accruing, it is difficult for doctors and loved ones to know how to deal with, and something that is not taught effectively if at all.

[pullquote]When irreversible conditions and losses are accruing, it is difficult for doctors and loved ones to know how to deal with, and something that is not taught effectively if at all.[/pullquote]

“Old age is not a battle. Old age is a massacre.” Taken from Phillip Roth’s novel Everyman, Gawande uses this quote to point out the flaws in our attitude to aging. Ultimately this is not a fight we can win. The lack of attention devoted to the subject of mortality in medical school according to Gawande was frankly alarming. He cites a single hour spent studying Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich as the primary component of this lesson on what it means to be finite. A lesson he now acknowledges he did not understand – for how can an aspiring young doctor, full of grand plans to save lives and ‘fix people’, contemplate what it means to help others when they cannot be mended?

In 1945 the majority of the population died in their homes. By the end of the 1990s, around 83% died in medical institutions such as nursing homes or hospitals; these places offer what they see as priority for patients: health and safety. This is perhaps the crux of the problem – this mismatch between the priorities of the patient and the priorities of the health system, or the family of the patient. A life prolonged, stretched out using machines, medications and trauma-inducing treatments is a quantitative approach to living, and often causes more suffering in the long run.

[pullquote class=”left”]this mismatch between the priorities of the patient and the priorities of the health system, or the family of the patient[/pullquote]

Dr. Gawande has said in interviews that he is not a natural writer, though there is little evidence of that in this book. Direct, engaging and often personal in tone, Gawande interweaves stories of his own patients and family, explores the current models of care such as nursing homes, hospices and assisted living, and earnestly embarks on the search for a better version.

As I read this book, I was reminded of the Hippocratic Oath itself, the promise historically undertaken by physicians to provide an ethical basis for their practice. Upon revisiting I noticed little mention of death or any preparatory advice. The Oath speaks of curing, healing and caring for the sick – very telling of a society fundamentally unprepared to deal with the end of life.

Being Mortal offers no definitive solutions, however it does raise some important questions. The author highlights the necessity for a more broad and in-depth conversation to be had both within medical institutions and in society about what it means to live a good life, and how this can be facilitated right up to the very end.